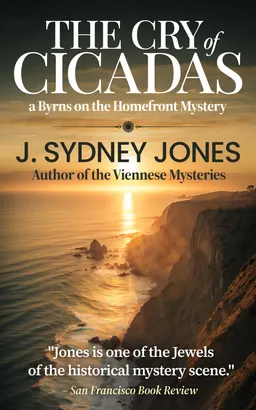

Nothing in the cry of cicadas suggests they are about to die.

- Matsuo Basho

Part One: A Matter of Loyalty

Chapter One

October, 1941

They first met Tadeo Suzuki not long after Max and his wife Elizabeth moved to San Ignacio. For days they’d surveyed available houses, escorted by Elizabeth’s realtor brother, Theodore, whom everyone but Max called Teddy. He somehow couldn’t use that name with the aristocratic-looking Theodore Schuyler, but Teddy’s looks were not finding them a house to live in.

At the end of the third week, Max decided to take matters in hand and check out the real estate ads in the local paper, the San Ignacio Reporter. And bingo, he found exactly what they were looking for: a one-story, three-bedroom on a double lot on the edge of town.

It was a hot day in mid-October when he and Elizabeth drove from the San Ignacio Inn to the viewing.

In New York he knew the seasons would be changing by now; leaves coloring in Central Park, autumn chilling the early morning air. Here it was still summer. Mid-eighties with Halloween around the corner and threat of war in the air.

“You’ll get used to it,” Elizabeth had told him when they were first considering the move. “If you ask me, winter is a highly over-rated season.”

Max, who had lived in New York City since birth, wasn’t so sure. Seasons had informed his life. Perhaps you were cut off from the land and its cycles in the city, but there were other reminders: in September, the Philharmonic and Metropolitan Opera would start their fall seasons; in winter, skating in the park was accompanied by the clip-clop of horse-drawn carriages on snowy streets; his favorite cozy restaurant just off Gramercy Park opened its sidewalk seating in April; fingerless gloves on the fancy women announced the arrival of summer. A thousand sights and smells that informed each season.

He was nostalgic, homesick even. But the move had been the right thing to do. Even curmudgeonly Dr. Rosenberg at Bellevue thought it necessary.

So Max was giving it his best try, looking for things to admire here.

He had five positives so far, and telling Elizabeth of this change of attitude produced one of her quizzical smiles.

“You might be right,” he said. “Seasons in general may be overrated and there seems to be plenty here to like.”

Then a broader smile from her. “How equitable of you. Plenty to like, as in…?”

He ticked off the list on his fingers. “The Pacific Ocean. The salt smell first thing in the morning and the way the water changes colors under different skies.”

She licked her forefinger, and checked off on an imaginary scroll. “I’ll give you that one. But watch out. You might start waxing poetic if you continue like this.”

He ignored this, continuing with his list. “The foothills east of town.”

She looked at him expectantly. “That’s it? Just hills? No description? Be honest. It’s the Cardoni winery up there that you really mean. Their table red.”

He shrugged, cleared his throat. “How about the historic downtown. All the brick shopfronts.”

“But more importantly,” she countered, “your musty used bookshop, ‘Just One More Page’.”

“You don’t give a guy a break, do you? Number four, local seafood, including freshly dug clams.” He paused for her rejoinder. Nothing came.

“And finally, yes, you can laugh at this one. But I’ve actually come to like the way a complete stranger will say hello to you on the street. It’d be irritating in New York but almost endearing here.”

Elizabeth shook her head, then gave him a peck on the cheek. “You’re becoming a local, Max.”

It was true. He was beginning to feel at home in tiny San Ignacio despite its lack of seasons.

A sixth favorite was working its way in, as well—the sometimes jarring, sometimes humorous blend of Spanish and English for place and street names.

Thus, they arrived early at the house on San Anselmo, just off James Street on the outskirts of town.

The owner, Max noted, was early, too, standing by the front door as if in anticipation. Max saw Suzuki was not a tall man, but his thinness made him appear so. He was hatless and his greying hair bristled up as if electrified by static.

Max always took in such details of appearance. They had come in handy during his twenty-plus years on the force.

They got out of their car and approached. “Mr. Suzuki?”

The man nodded. “Mr. Burns, I believe. And Mrs. Burns. Let us hope no mouse will disturb our plans.”

Max smiled at the reference. “Wrong Burns,” he said. “We spell ours with a ‘y’ not a ‘u’. You an admirer of the Scottish bard?”

“Not really,” the lanky elderly man said, moving a hand through his thick hair. “It is Mr. Steinbeck’s fault, you see. He has made unconscious poetry lovers of us all with that little novel of his from a few years ago. Of poetry in general, though. Yes, I am an advocate.…”

He paused as if catching himself from saying too much, a look of sudden sadness about his eyes. “But that is a different matter.”

Elizabeth at his side squeezed Max’s hand. It was something she did to show quiet approval of people or places. Max looked at her and blinked assent. He took an immediate liking to Tadeo Suzuki. Max saw a quiet strength to him and a certain grace, though he was dressed in dungarees and chambray work shirt as if he had just come from the fields. But Max too was adapting to the more casual dress code of California and felt a comfortable freedom with no tie binding his neck. Ties growing up in the Byrns household had been de rigueur; the only time he remembered his father—a medieval scholar at Columbia—without one during daylight hours was on his death bed.

“Would you care for a tour or should I let you wander on your own?” Suzuki asked.

“A tour, please,” Elizabeth said brightly.

Suzuki opened the door onto a pleasant sitting room with shiny hardwood floors, empty of any furniture. He drew the curtains to let the light in and led them first to the kitchen where Elizabeth nodded at the gas range and then down a hallway to the bedrooms and a full bathroom.

Max was pleased to discover that the house was in a U-shape, almost like a medieval cloister, around a central garden area that was now a barren patch. He was reminded of how, when he’d most needed it last year, his visits to the Cloisters in Upper Manhattan had soothed his soul.

They gazed at the area from the window of what was meant to be the master bedroom, Max figured. A room itself in an L-shape.

It would be Elizabeth’s studio, he immediately thought. She needed such a space for her art restoration work. Especially after leaving her career at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, leaving her colleagues and friends behind to help him recover. She deserved it.

“Needs work,” Tadeo Suzuki said, nodding toward the barren patch of ground outside. “Are you a gardener, Mr. Byrns?”

Elizabeth chuckled at this.

“I assume that means no,” the Japanese man said.

“Sorry.” Elizabeth tapped his arm reassuringly. “I should let you know that my husband has a decidedly black thumb. An excellent investigator, but not an ounce of compassion for poor plants.”

“An investigator?”

“Sounds grand,” Max said. “But I was really just a cop.”

“A noble profession,” Suzuki said.

“That’s what I’ve always thought, too, Mr. Suzuki,” Elizabeth said.

“But your husband thinks otherwise?”

“That’s another story,” Max said with a wry smile. “A different matter.” Echoing Suzuki’s own words earlier regarding his love of poetry; they both had secrets.

This brought a smile from the Japanese. “We may be a backwater, Mr. Byrns, but even here news of the Markham kidnapping did trickle down.”

Max felt his face grow red. Damn, this followed him like an albatross. And then the all-too familiar feeling of panic, the thickness in his throat, tightness in his chest. He took a deep breath, tried to divert his mind as Dr. Rosenberg had counseled. “Don’t believe all you read in the papers,” he said with false cheer.

They continued the tour, inspecting the other bedrooms and bath. Outside, Suzuki led in a leisurely but stiff-gaited walk that made Max think of a large shore bird, moving with quiet elegance as if parting waters. They surveyed the garage, in as pristine shape as the rest. Not even a spot of oil on the concrete floor.

“I have to admit, it’s in great condition.” Max spoke slowly, trying for normalcy, fighting back the wave of anxiety from mention of his former life. They moved on to the sundrenched, parched courtyard. “Like nobody’s ever lived here.”

“No one has,” Suzuki said with what seemed a touch of emotion. “Not a single soul since it was built eight years ago.”

“It just sat here vacant all that time?” Elizabeth asked.

“Oh, I would come periodically to air it during summer days or turn the heat on in the winter. But otherwise, vacant.”

“What a shame.” Max took deep breaths. Focus, he told himself. He looked around the parched ground trying to imagine what it would look like with a medieval garden installed. “When did you buy it?”

A wry smile from Suzuki, then, “I had it built.”

That took a moment to sink in.

“You mean,” Max said, “built to be sold or to live in?”

“Ah, I see now what your wife says, Mr. Byrns. A true investigator. You ask the right questions. … No, not as an investment. To live in. But we didn’t.”

Max was about to ask why, but stopped, fearful of some family tragedy.

Elizabeth, however, seemed to feel no such compunction. “Why ever not?”

Suzuki tipped his head. “My wife, you see.”

“Oh, I’m so sorry,” Elizabeth began, blushing at her lack of tact.

“No. No reason to be. I built it for her. For Kyoko, my companion of nearly forty years. It was her that helped make me, to make our family what we are. And she’s never asked for even the tiniest bit of luxury. We still live in the small house we bought all those years ago. So, I wanted to surprise her. Spoil her for once. But when I brought her here, she looked timid, like a tourist visiting a fine country home. It is difficult to explain. She is a simple woman, a humble woman. She came from a small village…”

“She felt it’s too fine for her,” Max said.

Tadeo Suzuki nodded firmly. “Too fine for a humble farming family. For a Japanese farming family in America.”

Max could hear the edge of bitterness in him, and was reminded of the hard road the Japanese had had to endure in California, denied citizenship, their immigration restricted, always looked down on as the mistrusted foreigner.

“You’re a farmer then?” said Elizabeth

Another nod. “I was. My sons James and Hiro have taken it over now. They say I have earned my rest. So, I please them by acting happy to spend my days playing chess or designing the perfect Zen garden.”

“It doesn’t sound like you’re any happier to be retired than I am,” Max said. “You know, I also play. Perhaps a game … ?”

“I look forward to it, Mr. Byrns. As for my sons, I actually think they believe I am too old for the big farm I built. Too old and in the way.”

They were silent for a time. Max thought he had his nerves under control now. Again, he tried for normalcy, like Dr. Rosenberg had counseled, forcing himself to reflect on how oddly similar their situations were. It wasn’t their ages, for Max was at least a decade younger. But after what happened that night eight months ago in New York, he too felt in the way at the police department. He’d become more introspective, thoughtful. Some called it second-guessing.

And second-guessing could get a cop killed.

And now it hit him again; no controlling it this time. Blind fear. Shortness of breath. He’d been having the panic attacks and dream less often and was beginning to feel out of the woods. But now, awake, the dream came back, the endless loop that played in a grainy black-and-white flash when he reached deep sleep.

As a NYPD captain he should not have even been there, but he knew the kid, David, a childhood friend of his own son, Philip. Max knew the family and their shame. This most recent bit of stupidity—joyriding and evading an officer—on top of a pending vandalism charge could earn the eighteen-year-old five-to-ten. David was fragile, Max knew. And explosive.

Max wanted to be present at the arrest, to reassure the youth somehow. But here was Detective Mickelson pounding on door 403 in the middle of the night, shouting for those inside to open up before he kicked the motherfucker in. And the sound echoed in the narrow confines of the hallway of the apartment complex for all the neighbors to hear.

Brewing shame. Stoking fear. Max felt the heat of anger toward Mickelson, felt the burn of shame for the kid and his family.

When the door flew open, it took Mickelson by surprise, but not Max. He could see the Smith and Wesson .32 in David’s hand and knew it was too late now for empathy.

He managed to call out “Don’t do it,” before jumping between wide-eyed Mickelson and the gun.

Max didn’t so much feel the shot as hear it, but the impact of the bullet knocked him across the hallway and against the opposite wall.

There were more shots, but Max heard them only as if from the bottom of a long and deep well, and then Mickelson was calling out over and over in the stairwell, “Officer down, officer down!”

The vivid vision disappeared now. He blinked, took more deep breaths. He was certain he was not a coward. During his career with the NYPD, he’d faced down some of the most vicious criminals in New York. But the effects of David’s shooting still lingered. He’d gone into early retirement partly because of the gunshot, but also its psychological toll.

“You’ll get your stamina back,” old Dr. Rosenberg had assured him.

‘Stamina’ was, Max finally understood, code for courage.

Max had gazed out at the East River from Rosenberg’s Bellevue Hospital office.

“When?” he’d asked.

Rosenberg had sighed. “You’ve suffered a trauma. Every bit as fierce as that raw wound in your chest. Some wounds take longer to heal than others. I know your history, I’ve read about your exploits in the Sun, just like much of the rest of the country has. How you personally tracked down the kidnapped Markham baby, or took on the Irish mob and shot it out with Little Caesar Malone.”

Max had set his jaw as he listened to this. He was proud of his police work, but the phony celebrity that had come with it made him angry and ashamed. “The papers needed a hero,” he’d explained to Rosenberg. “I didn’t ask for it.”

“But you got it. Maybe you even earned the reputation as a cross between Superman and super G-man. But you might have to learn to live that reputation down rather than live up to it if you want to get healthy.”

“Max?” Elizabeth said now, worry in her voice, a hand to his forearm. He forced a nod. “Sorry. Million miles away.”

Suzuki smiled at him, reassuring, open, as if he understood. “Do you like strawberries?”

Chapter Two

Max signed the papers that same day.

And he also began an unlikely friendship with Tadeo Suzuki, who insisted on skipping escrow and other costs in a deal that was between gentlemen. A handshake was what Tadeo Suzuki used to bind the bargain.

He and Elizabeth had sold all their furniture in New York, ready to start a new life in California. In a way, this made it simpler—no long-distance movers to wait for. But it also made for complications. San Ignacio was a friendly little town, the sort of place you felt you could leave doors unlocked at night. But not exactly a shopper’s paradise, as Elizabeth had been quick to point out to Max.

“When we summered here, we’d be sure to bring suitcases packed with our favorite New York things—for Teddy that meant bagels and plenty of them. Of course, they’d go stale before he finished them, but he still refused to share. Served him right. Daddy had to have his Antonio y Cleopatra cigars, and the Mater insisted on silk threads for her embroidery. Things you’d never find in San Ignacio. You’d have to go to Monterey.”

“And you?” Max asked. “What was your treasure trove?”

“A fresh supply of Winsor and Newton oils, of course.”

So, it was to Monterey and San Francisco they traveled in search of new furnishings. And with each trip they would bring back some new prized piece—or pay for its delivery if too large for their Oldsmobile wagon. Tadeo Suzuki invariably would arrive not long after to show his approval of their purchases, to cajole Max into a game of chess, to advise Elizabeth on the best places locally for meats, vegetables, hardware.

If in New York, Max would have felt uncomfortable at these continual unannounced visits.

But this was San Ignacio and Max was finding a new rhythm. The temperature had lowered now into November, trees surrounding the house were actually taking on autumn foliage, and Tadeo Suzuki had become a friend and helper rather than a nuisance. Each time, he came bearing a gift: the perfect work stool for Elizabeth once he learned she was an art restorer; a pair of cherry-wood handle secateurs for Max in hopes of turning his black thumb green. Another time, a ball of fluff under his arm turned out to be a yellow lab pup so cute and cuddly that even Max, whose only pet ever had been a gold fish, wanted to hug it.

“For the lady of the house,” Tadeo pronounced. “A house is not a home without such an animal.”

He held the pup out and now Max and Elizabeth saw its large paws which foretold an equally large dog when full-grown.

Elizabeth, whose family had horses and dogs, teared up at the gift.

“Tadeo, you sweet man. How did you know?”

It was the only time Max saw him at a loss for words, touched by Elizabeth’s response to his handsome gift.

“Looking at those feet, ‘Tiny’ seems a good name for him,” Max said.

“Her,” Elizabeth corrected. “And I agree. A sense of irony is needed here.”

As they got to know Tadeo, they also slowly learned of his life, arriving in California from Japan in1902 at the age of twenty-two and going to work in the fields as other Japanese men of his generation did. A hard life and Tadeo told them he was determined to make something of himself. He soon married, then three children: older son James, then Hiro, and finally the daughter, Miriam.

“I am worried about her,” Tadeo confided. “Still no husband. I do not want her to sacrifice her happiness to take care of aging parents.”

But his ambition paid off.

On another visit he told Max of his gradual rise in the world.

“We Japanese were welcomed here at first. The Chinese had been excluded and industries and farms needed new workers. But then, as more of us arrived, we became the new danger. The yellow peril not to be trusted.”

“And immigration from Japan was cut off,” Max said. “In 1907.”

Tadeo nodded. “Correct. It is a pleasure to talk to someone who has a sense of history. And because I was not born here, I am unable to become a citizen. But I and other Japanese were able to lease land. We did so cooperatively and often we had the need of white landowners as intermediaries. In this way, I and a man named Arthur Pinkus built a successful strawberry business, PurGro Strawberries. It became known throughout the state.”

Tadeo fell suddenly silent, contemplative.

“But?” Max asked.

“Yes, my friend, there is a ‘but.’ Most of the profits went to Mr. Pinkus. Still, I stayed with him, awaiting my chance. And it came when my oldest son, James, who was born here and is a citizen, reached legal age. Then we could begin to buy our own land.”

And buy it they did, as Tadeo went on to relate. “First, we purchased twenty acres by Pulgades Creek. That’s about a dozen miles south of here. We were finally able to farm independently, the Suzuki family farming Suzuki land and keeping the profits of our labor. It wasn’t easy, of course. Long days in the fields, back-breaking work, but it was worth it. It was ours. Can you imagine the satisfaction we felt working our own land, finally? And after the first successful harvest, we were able to buy thirty more acres south of the main water tower.”

Max could see the pride in Tadeo’s face as he told of this.

“And so it went throughout the 1920s,” Tadeo continued. “America fell into the Great Depression, but people did not stop eating strawberries. We became S and Sons Strawberry Farm and were able to buy more and more land, becoming the largest strawberry farm on the central coast of California.”

His face lit up as he said this.

“How’d you ever save up enough money for the original purchase?” Max asked.

Tadeo shrugged. “We Japanese are quite inscrutable, or haven’t you heard?”

Which explained nothing, but Max did not press. It did make him curious, however. Made him feel his new friend was keeping something from him. Tickled the dormant curiosity of the former police detective. The problem with being an honorable man; you can’t lie worth shit.

“Invisibility, Mr. Byrns,” Tadeo added. “That is what I aim for. That my white neighbors do not notice me and become jealous.”

Several weeks later, Tadeo came with a roll of paper in hand which, when spread out on the kitchen table, displayed the plans for a garden.

Tadeo looked at it proudly. “You spoke of the beautiful gardens at this place in New York—”

“The Cloisters. Yes. Beautiful medieval gardens.”

“Well, this is medieval in a way, too, my friend,” Tadeo said. “Medieval Zen. It was what I had planned for that wasteland out there.” They looked through the kitchen window at Tiny doing her business in the scorched earth.

“I can see a quiet and peaceful preserve there.”

“This looks fabulous,” Elizabeth said, surveying the plans.

Max agreed, but hesitated, wondering how he would ever find time or strength enough to build it.

“I would feel honored if I could work with you on this,” Tadeo said.

“You and me?” Max asked.

“That’s a wonderful idea, Tadeo,” Elizabeth said. “But we can’t be taking advantage of you like this.”

“Nonsense,” Tadeo said. “It gives an old man purpose. It is I who should be thanking you. Kyoko thinks so, too. So I am no longer underfoot every day.”

Elizabeth smiled at this. “Please tell your wife that I am of the same mind.”

Tadeo arrived several mornings later, shortly after a delivery of three yards of 3/8th inch pebbles from Mancusi Landscaping. He was driving a flatbed truck with “S and Sons Strawberries” painted on its doors. From it emerged a good-looking young man dressed in chinos and sweatshirt, tall and powerfully built.

“I have brought a helper,” Tadeo announced. “My grandson, Jimmy. Hiro’s son. Home now from San Jose State, on his way to Hawaii. But I have enlisted his aid for the day. Not without an argument, I add.”

Jimmy rolled his eyes at this, then smiled. “I’ve heard a lot about you, Mr. Byrns.”

Max and he shook hands. “What’s happening in Hawaii?” Max asked.

“Football. The San Jose State team is playing a charity event.”

“What position?”

“End.” He quickly added, “And no, Grandfather. Not end of the bench.”

“They become too quick for you, have you noticed?” Tadeo said, smiling.

“That’s the way it is with Philip, as well. Too big to tease.”

“This is news,” Tadeo said, his eyes sparkling. “I had no idea you are a father.”

“You didn’t ask. But yes. And he’s about your age, Jimmy.”

“Where does he go to school?” Jimmy asked.

Max felt his usual anxiety bubble up. “Actually, he’s left school. He’s in the Army Air Corp.”

Tadeo nodded at this. “You look concerned.”

“Well, these are uncertain times.”

“It won’t come to war, I am sure of that,” Tadeo said.

Jimmy smiled but looked as if he did not agree.

A moment of awkward silence before Tadeo asked, “Where is your lovely wife?”

“In the studio. A restoration commission from an art dealer in Carmel and she’s quite happily at work.”

“Then I suggest we also get happily to work. Jimmy, the wheelbarrows, please.”

Tadeo had brought tools and equipment strapped onto the flatbed and while Jimmy got them down, Tadeo again checked their work on the garden area where they had already staked down landscape fabric as a weed barrier.

Tadeo rubbed his hands together. “Now for the hard work.”

Next several hours were a blur of activity for Max, as he manned one of the wheelbarrows, filling it with pebbles and wheeling it to the position Tadeo indicated and then dumping. As he left for another load, Jimmy would come with his load and Tadeo would spread the rock with a bamboo rake.

Max had not worked this hard in years, and soon his chest wound was pounding with pain. But he did not want the others to notice. Tadeo, however, was observant.

“Perhaps a break for lunch. I have a grumbling in my stomach that demands attention. I know just the place.”

They fetched Elizabeth and after introductions between her and Jimmy Suzuki, they all piled into the Olds and Max followed Tadeo’s directions to the Town and Country Café. They devoured tuna sandwiches and burgers and gulped down several cups of coffee, joking as they did so about their Medici Zen garden taking shape.

After an unsuccessful attempt by Tadeo to pay for the lunch, they delivered Jimmy at a friend’s house, went back to work on the garden, and let Elizabeth get back to her restoration job.

By three, the rocks were mostly laid and raked into swirling designs by Tadeo. They’d still need flagstone pathways and larger boulders as well as some greenery, but Max now could see light at the end of the tunnel, and was surveying the garden with delight.

Though already early December, the day was mild and Elizabeth came out with a tray holding two beers. Max gladly took his and then noticed Tadeo glancing at the other in discomfort.

“Would you rather have tea?” he asked

“That would be good of you, yes. I do not wish to be a difficult guest, but you see I do not drink alcohol. Not a drop in forty years. But that is another matter.”

“One day you must tell me about these other matters of yours,” Max said.

“Yes, and one day you must tell me why a man of your age and reputation should retire.”

“Reputation?”

“As I told you the first day we met, news of the Markham kidnapping was reported even here. You did a brave thing, Max. It is nothing to try and hide.”

Max nodded, said nothing. Part of his past. But mention of the kidnapping set him off again. He felt a surge of panic, but managed to squeeze it back into its black box.

The next two days they put on the finishing touches, with visits to Mancusi for larger boulders and low shrubbery for the periphery. The final day Tadeo arrived with a bonsai pine he had grown himself as a centerpiece to the garden.

“This is too much, Tadeo. Too generous.”

The older man shook his head. “Generosity is nothing more than good will, Max. It does not bind you.”

They sat on two low birch stumps they’d found at the landscaping yard and appreciated the serenity. Tiny came wiggling up to Tadeo, licking his hands.

“About my other matters—”

“You don’t need to tell me,” Max interrupted.

“I know that, and that is why I would like to. It has to do with why I came to America. How one incident changed my life. I had a friend in Japan. A man I thought was my true friend. I have not allowed myself another such friend since that time. Not until we met, Max.”

Max felt his throat catch. “That is good of you, Tadeo. I look on you as a true friend, as well.”

“But a mediocre chess player.”

They exchanged smiles.

Tadeo went on.

“You remind me of him. He was like you in many ways. A big man. And a thoughtful person. A man I felt I could trust, a schoolmate at the Normal School. But this person—I called him Basho, a nickname, you see…”

“The poet.”

Another smile from Tadeo. “Yes. I wanted to be the poet then, but to my friend I gave the honor of that name, hoping he would help me convince my parents against their wishes for me. They wanted me to become a soldier, you see, but I was not made of that stuff.”

“Where was this?” Max asked.

“Japan, of course.”

“I mean where in Japan.”

“Oh, sorry. Yokohama, my former home.” He paused, looking up into the blue afternoon sky. “But Basho betrayed me. Instead of interceding on my behalf with my parents, he let my father convince him to become an informer for the military police, the Kempeitai. It all came to a head one night when I was having dinner with Basho and his parents at their home high above Yokohama harbor, a place they call the Bluff. I had been drinking heavily since my father told me of Basho’s involvement with the Kempeitai, chiding me that I did not have my friend’s ardor. And that night, again drinking too much sake. Suddenly I had to have air and fled, going to the very edge of the Bluff, and when Basho came looking for me, we got into a terrible fight. I was much smaller, not a fighter at all. But that night I had a savage fury, knocking him to the ground and beating him unconscious. I feared I may have killed him. Next day I took ship for America, and I vowed never to touch alcohol again and to live my life in atonement for what I did to Basho.”

He sighed, his shoulders slumping. “Not a pretty story, is it, my friend.”

Max was about to respond when Elizabeth came out. “There’s a call for you, Tadeo.”

It was his son to talk about a business matter.

After Tadeo left, Elizabeth said, “For a man with a new garden, you’re looking damn sad.”